How to improve website navigation with testing and analytics

Hint: it’s not by using the same tips that everyone is reposting since 2012. So what’s the true improvement? It’s testing with your audience.

Written by Tomasz LisieckiTo be clear, I’m not discouraging the use of best practices. There’s merit in all of them. It’s often our default, too – guilty as charged.

But just doing a dozen of things that “work for everyone” isn’t the way to go. Some of the changes will work for your site, and some will hurt it. You’ll never know which is which. More often than not, this will bring you back to square one.

But we need these best practices in our toolkit to know what to test. Here’s a recap of the solid advice that you may want to test later on, when we give you navigation testing tips.

Five best practices for website navigation

- Keep it under seven items; ideally between three and five.

- Put important items first and last.

- Avoid complex dropdowns. Unless the structure of your site requires a comprehensive dropdown, less is more. Huge menus are usually reserved for ecommerce sites.

- Make good use of the footer. Visitors that scroll this far are either engaged or lost. Give them access to as many important pages as reasonably possible.

- Include the main Call To Action in the navigation bar.

I know it’s tempting, but we agreed you won’t run off to implement these right away. Instead, let’s reveal the two tests you should use. They work in tandem, and as standalone tests.

You can use it to evaluate the current navigation, test a new structure, or even get people to help you come up with the navigation categories.

Two ways to test your navigation

If you have the data and hypotheses for navigation tests, this is all you need to get started. One of the tests can also find issues with your existing nav bar.

If you need more ways to find problems, we cover them later. For now, let’s run your first tests!

Learn how people organise your content

It’s easy to assume that a certain page should go into your “Products” tab. But is that really the case? That’s where card sorting comes in. It’s a way for testers to put information (in this case, your pages) into buckets.

Open card sorting

Open card sorting gives people a blank canvas, with just a list of pages (or content) to group.

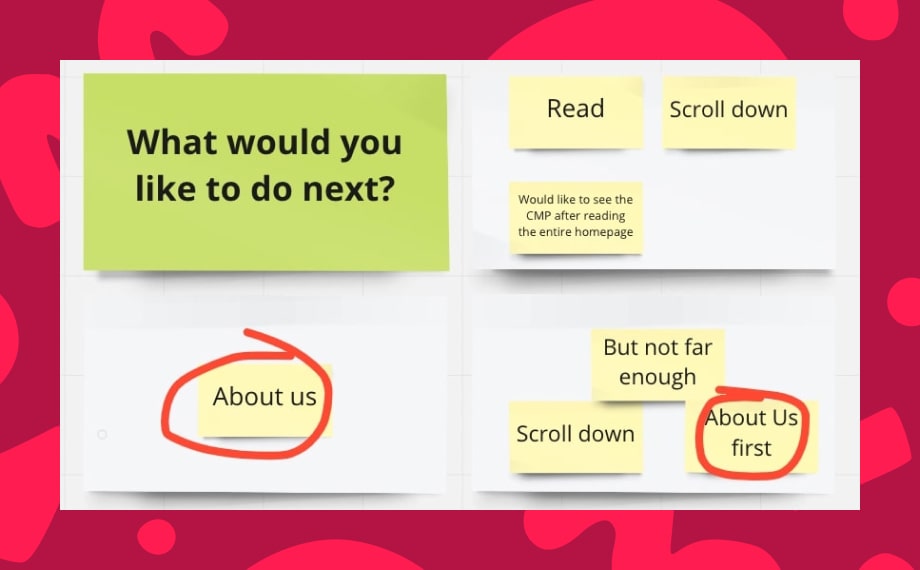

You ask them to group the information together, and then also come up with their labels. This is a great way to start your work on website navigation, as you’ll discover the thought process of your audience.

Closed card sorting

In closed card sorting everything is pre-defined.

If you’re set on having specific dropdown labels, users will help you decide where to put each page. It’s restrictive, so we’d recommend leaving it for later stages of testing. But it’s a good way to spot bias in your thinking. Maybe you were convinced this one page should go into Solutions, but everyone expects it elsewhere?

Hybrid card sorting

In the hybrid approach, you give users the list of pages and labels, like in closed card sorting. But you also allow them to come up with their own labels if needed.

This is my favourite when the hypothesis is that the navigation is mostly correct. It allows you to validate that, but also gives people freedom to come up with better groups.

Check if people know where to look for pages

Card sorting helps build the navigation, but it’s not the best at validating if your information is findable. That is where tree testing shines. This test asks people to complete tasks using a fixed navigation structure.

An example would be:

“You are looking to renew your TV licence. Where would you find the information?”

Remote tree testing is very popular. It measures the number of clicks and the time before the user selects an answer. You also get detailed information on the paths they explored.

If it takes a minute to complete a simple task, you have a problem. Likewise, if someone has to click through all of your dropdown menus to find the page, it would be a red flag.

Doing it in person has several advantages, including higher-quality data and direct access to the participants. The speed, cost, and ease of access to remote testing outweighs those benefits in most cases.

How to use different navigation tests for best results

Each individual test is great at solving one problem. But how do you combine them to be more thorough?

Tree testing after card sorting

Regardless of your card sorting test of choice, tree testing helps validate the outcomes of card sorting.

Once you agree on a structure after card sorting, run it through a tree test. See if people can actually find the information.

Solving a problem is a different mindset from categorising information. What might sound obvious when you see all available pages, might not be as intuitive when you only see a few high-level labels.

The outcome of tree testing isn’t always moving a page to a different menu. It’s possible that the bucket is right, but the label doesn’t work. Make sure to structure your tests in a way that covers both options.

Testing existing navigation

Tree testing sounds like a no-brainer for existing websites. Getting a hundred people to do several tasks using the navigation alone is eye-opening. But you can use card sorting to a similar effect.

Running it through a closed card sorting test will validate if your groups make sense. If you opt for a hybrid test, you’ll get suggestions of the new groups or labels on top of that.

Narrowing down on the dropdown labels

Before you jump into tree testing, you can go through multiple card sorting tests. Each of them has a slightly different purpose.

We often start with closed card sorting using either the current website navigation, or the new structure we came up with.

This leads to a few possible outcomes:

- People could categorise most pages like we did. Hooray. 🥳

- Pages will end up in different buckets than intended. There’s work to be done.

- Some of the pages end up as not categorised. That’s even more problematic.

Once we know the nature of our problem, we can target it with another test.

If just a few pages ended up under the “wrong” label (scenario 2), we can run a tree test using that new structure.

Open and hybrid card sorting is great for scenarios 2 and 3, since it will help you figure out where people expect the “orphan” pages.

With option 3, you shouldn’t even think about tree testing just yet.

The ultimate navigation test sequence

Most of the time, tests go well, but not perfect. After trial and error, our default approach is as follows:

Closed card sorting -> Open card sorting -> Hybrid card sorting -> Tree testin

First, we figure out which pages and labels complicate things.

Next, we get an understanding of where people would put them if there were no limits.

Based on these two tests, we can estimate a useful structure.

We present it to another group of testers, while giving them the flexibility of a hybrid test. Quite often, most pages will end up in the “right” buckets at that point.

Then we put it through the paces in a tree test. Depending on the size of the navigation, we give testers up to 10 tasks. After they’ve clicked through the dropdowns a few times, people become familiar with “what’s where.” This has diminishing returns.

“But what about moderated user tests?”

Moderated user tests are expensive.

If you have the resources, you can moderate both tests I’ve mentioned. It gives you more control and context, especially since you can have a conversation with the tester and follow up with questions.

Going beyond that increases the scope of your test. Card sorting and tree testing are great because they focus on the logical structure of navigation.

A moderated user test of a bigger prototype introduces distractions. These result in additional insights, which is great. But if you’re only looking to test the navigation, this can be inefficient.

There’s another end to the stick, though. The card & tree tests focus on logic, but we know people navigate websites intuitively. A strict test like that doesn’t reflect on how they would use the website in natural conditions.

Broad moderated tests don’t reflect that environment either, but it’s closer to the “real thing”.

The decision depends on the full context of testing, so it’s impossible to say “don’t use moderated tests” or “do use moderated tests.”

How to find navigation problems that justify testing?

Card sorting can be a good way to identify problems, especially the closed version. If people struggle with the test, you know the current labels don’t work. But what else can you do before testing?

We love user feedback forms, but they’re prone to false-positives. It’s rare to know if the visitor reporting issues is from your target audience.

Having a problem flagged by a single prospect is also problematic. When and how do you decide to take action? Spending resources on tests based on one person is the equivalent of launching changes on a hunch.

But there are two ways that can work better: analytics and session recordings. These tools are not without flaws. They are also challenging in terms of the traffic quality, but make up for it with quantitative data and filters.

You can isolate visitors based on the pages they read and the engagement rate. This gives you much more context than an anonymous report.

Finding navigation issues in analytics

Analysing specific navigation elements, such as the top menu, usually isn’t possible without a bespoke setup. But you can get “close enough” by checking the paths users take on your website.

We’ve outlined how to analyse navigation in GA4. Most alternative solutions have similar features.

The quickest way to spot issues is looking at the pages that people don’t visit when going through a specific page.

By looking at our Home page, I’ve requested to remove one navigation feature from our website. It was getting no traffic at all, so why bother?

Watching recordings of how people navigate your website

You can get started with affordable CrazyEgg plans, the free tier of Hotjar, or even the completely free Microsoft Clarity. These tools are great at spotting u-turns and rage-clicks, which show frustration and poor navigation structure.

If you’re using mega menus, you can see how quickly people find a page to click on.

Do they click through all the dropdowns? This means they’re either exploring, or more often, simply lost.

Even worse if they click them all and then have to go back a few times.

What about dropdowns that get opened but never clicked, or maybe ignored altogether?

After watching a bunch of recordings, you should be able to spot patterns like these. Knowing the different testing methods you’ve learned before, you’ll be able to validate your suspicions and find a better solution.

Happy testing!

Originally published Aug 13, 2023 10:50:02 AM, updated November 4 2025.